Intervention Program for High Sodium Intake among Indonesian Adults in Urban Area

This public health intervention was designed as part of assignments on Disease Prevention and Health Promotion subject. As this is my first time designing a public health program, there are still some lacks in some aspects.

A. Introduction

1. Magnitude and Burden

Adults in Indonesia have high intake of sodium. Research shows that more than 4 out of 5 people consume more than 5 g/d of salt (Sari et al., 2021), specifically 5.9 g/d in women and 6 g/d in men (Sari et al., 2021). That amount of salt is considered as high since the dietary recommendation for salt intake is only 5 g/d salt or 2 g/d of sodium. This recommendation was released by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia referring to the sodium intake guideline by the WHO (WHO, 2012). High sodium consumption significantly associated with the higher blood pressure and high risk of cardiovascular diseases, such as stroke and coronary heart disease (Aburto et al., 2013). In Indonesia, the prevalence of hypertension rises from 25.8% to 34.1% in span of 5 years from 2013 to 2018 (Kementerian Kesehatan RI, 2019). Cardiovascular disease responsible for 30% of all death globally and the leading contributors of disability (WHO, 2007). Therefore, identifying the root cause of high salt consumption is essential as it will be beneficial to save the health system.

2. Target Population

Indonesian adults living in urban area will be the target population as the prevalence of hypertension is higher compared to rural areas, which is 37.25% and 27.8 respectively (Astutik et al., 2021). Moreover, the risk factors of hypertension are urban areas are dominated by modifiable risk factors, for instance, diet and lifestyle, in contrast to rural areas which are dominated by non-modifiable risk factors, such as age and sex (Astutik et al., 2021). Align to that finding, a study also found that salt intake has a bigger impact on hypertension in urban areas compared to rural areas (Subasinghe et al., 2016).

3. Prioritised Risk Factor

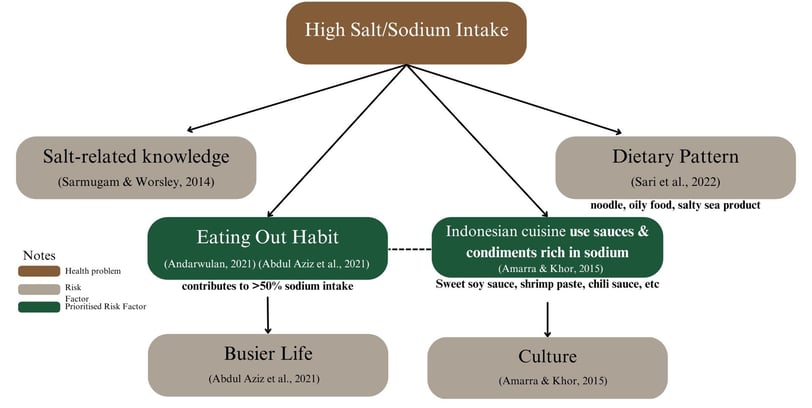

Risk factors of high sodium intake among Indonesian adults in the urban arena are varied as drawn in the diagram below:

Based on the diagram above, high sodium intake is caused by low salt- related knowledge, eating out habit which contributes to more than 50% of sodium intake, the use of sauces and condiments rich in sodium in Indonesian cuisine, and dietary pattern that consist of instant noodle, oily food, and salty sea product (Abdul Aziz et al., 2021; Amarra & Khor, 2015; Andarwulan et al., 2021; Sari et al., 2022; Sarmugam & Worsley, 2014).

Based on those risk factors, eating out habit and the use of rich sodium content in sauces and condiments will be prioritised. Urban adults are developing eating out habit as they have busy life that makes them unable to prepare their own food (Abdul Aziz et al., 2021), and end up contributes to more than 50% of their sodium intake (Andarwulan et al., 2021). While eating out, despite urbanisation, Indonesian tend to eat at a local restaurant that served Indonesian food, instead of coming to a western restaurant (Amarra & Khor, 2015).

The problem is that Indonesian foods use sauces and condiments that commonly contain high amount of sodium, such as sweet soy sauce, soy sauce, oyster sauce, MSG, premix seasoning, etc. Even “kecap manis” or sweet soy sauce, that sometimes people may not recognise it to contains high amount of sodium due to its sweet flavour, can be found in almost every household and responsible for the high sodium intakes (Andarwulan et al., 2011).

4. Goal and Objectives

a. Goal

To reduce sodium intake among Indonesian adults in urban area into <2000 mg/day

b. Objectives

- To reduce sodium content of sauces and manufactured condiments into

<140mg/ serving.

- To provide low sodium environment for Indonesian adults to eat out by turning restaurants into “low sodium option” restaurant.

To be able to reach the goal, objectives are created to address the risk factors. Currently, sweet soy sauces and chili sauces that are commonly used in Indonesian cuisines contain more than 1,300 mg/100g even 1800 mg/100 g, higher than the WHO global sodium benchmark that is only 680 mg/100 g (Istiqomah et al., 2021; WHO, 2021). Therefore, sodium content in sauces and manufactured condiments are expected to be reduces into <140mg/serving so it can be labelled as low sodium products (Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Examination of Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols. et al., 2010). Providing “low sodium option” restaurant is essential to provide safe environment for Indonesian adults in urban area to enjoy dining out without necessarily having excessive sodium intake.

B. Intervention

1. Current and Available Option for Intervention

Reducing salt intake can be done in three main areas, including food production by food reformulation to lower the sodium content, consumer education, and environment changes to ensure that low sodium products are easily accessible for consumers (WHO, 2007).

Current intervention addressing high sodium intake in Indonesia is done through health education methods by NGOs (Non-Government Organisations) and the ministry of health through various media campaigns with the main message is limiting salt consumption into 1 teaspoon only (Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia, 2022). Besides, the government also obligates food industry to put salt content on the nutrition facts label in 2012 as environmental change strategy (Batcagan-Abueg et al., 2013). However, labelling through nutrition facts is not effective compared to traffic system labelling (Hyseni et al., 2017).

Interventions addressing high sodium content on food products have been conducted in a few countries, as follows:

a. Mandatory salt reduction program

Mandatory salt reduction program has been conducted in several countries, including Argentina, Finland, South Africa, Greece, etc. Some of them targets only bread while some others target a wider type of foods including processed meats, cheeses, canned fish, or other foods that are known to be the source of sodium in their diet (Santos et al., 2021). This program is thought to be more effective than voluntary program as all company must comply, so consumers have no other choice than consuming those sodium-reduced products (Regan et al., 2017). However, it requires strong political support and long legislation process that potentially delays the implementation (WHO, n.d). A modelling study conducted in Singapore settings shows that mandatory salt reduction of 4g/day will avoid 24,000 incidences of CVD in 30 years. A great number according to Singapore population size (Tan et al., 2021).

b. Voluntary salt reduction program

Voluntary salt reduction program has been conducted in 36 countries including Ireland, Australia, Korea, etc (Trieu et al., 2015). This strategy is easier to be done as it only need shorter time to develop and implement as it will be easier to get political support (WHO, n.d). However, as it is voluntary program, monitoring need to be conducted intensively to ensure that the program is progressing well. In Australia, this voluntary salt reduction with incentive is effective to encourage industry to reduce salt in processed food (Cobiac et al., 2010).

c. Food labelling program

This strategy is implemented by several countries including Lithuania, Latvia, Norway, Sweden, etc. Usually, the label comes in the form of logo, symbols, traffic lights, as well as (Trieu et al., 2015). This program facilitates people to make healthier choice. However, there is a possible assumption by society that low sodium product has inferior taste compared to regular product (Regan et al., 2017). A study in Finland found that the mean salt intake reduced by 2.3 g in men and 1.7 g in women if people only choose low salt product (Pietinen et al., 2007).

2. Proposed Intervention

Primordial level of intervention through voluntary salt reduction program with labelling will be implemented to tackle the high sodium intake among Indonesian adults in urban area. As consumer education and environmental change has been conducted by government and NGOs, it is the time to do intervention in the food production area by doing product reformulation and labelling to create supportive environment for Indonesian adults in urban area to reduce their sodium intake.

Even though Indonesian adults in urban area is the target who are expected to experience salt intake reduction, intervention will not directly target them. To achieve the first objectives, voluntary salt reduction program and labelling will target sauces and manufactured condiments companies, mainly for companies which brand are widely used. To achieve the second objective, program will target local restaurant in urban area, especially busy restaurant as it potentially feeds many people.

This intervention is thought to be feasible for a country who never done any salt reduction program as it will be easier to get political and industrial support since they can rebrand as healthy product and gain more market. In the future, the program can be prolonged or shifted into mandatory program after people’s taste bud adapt to low sodium product (Cobiac et al., 2010).

3. Intervention Strategy

intervention will be conducted in two stages, as follows:

a. Stage 1: Reducing sodium content of manufactured sauces and condiments.

At this stage, intervention will be conducted by providing incentives for sauces and manufactured condiments companies to reformulate their product so the amount of sodium content can be reduced into <140 mg/serving. Companies that are successful in reducing the sodium content will be labelled as “low sodium” product. Incentives are provided to encourage companies to reformulate their products. The amount of incentives will be adjusted according to the scale of the company. The benefit of having low sodium content for the company will also be promoted since it allows them to rebrand their product as healthier choice for consumers and potentially gain more consumers.

b. Stage 2: Providing low sodium environment for people to eat out.

At this stage, intervention will be conducted by encouraging restaurants to use low sodium sauces and condiments without changing their recipe, in terms of adding the amount of product. For instance, if their recipe said to add 1 tablespoon of soy sauce, they should also do that with the low sodium product. Incentives and “low sodium option” label will be provided for restaurants that are successfully change their regular sauces and condiments into the low sodium products. The benefit of having low sodium will also be promoted.

C. Evaluation Design

1. Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation is a process to identify complexity of the problem, understanding the target, as well as potential intervention that will be carried on. This is an important process that will help to develop implementation strategies as well as evaluation plan (Elwy et al., 2020).

In this case, formative evaluation will be done to understand the excessive salt intake problem, the magnitude and burden of this behaviour, and the risk factor that underlying this problem. It is also important to understand what has been done in other setting, what is appropriate in Indonesian setting, limitations, and barriers of intervention. It can be done through literature review and consultation with academics. As this program will involve food industry, understanding stakeholders’ perception through focus groups discussion is important to predict the potential acceptability and getting insight to develop the intervention. It is also the stage to define target intervention in term of the criteria of companies and restaurants that will be involved.

Conducting modelling study will be beneficial to decide how much sodium should be reduced to gain expected benefit for the health of society along with budget forecasting and economic evaluation to ensure the program is feasible and worth to implement.

2. Process Evaluation

Process evaluation is conducted to monitor if the program is implementation as it planned (Dehar et al., 1993). Process evaluation is important to conduct as it can show how implementation lead to the program impacts and outcomes. It helps us to understand why a program is success or fail. Therefore, it is essential to define what are considered as successful implementation of the program (Saunders et al., 2005).

Some aspects to consider that the implementation of this program is successful are as follows:

a. Incentives offer and salt reduction proposal reach 70% of sauces and condiment companies.

b. Incentives offer and proposal of low sodium product usage reach 50% restaurants.

c. Participatory level of companies reaches 30%

d. Participatory level of restaurants reaches 20%

e. The program runs according to the timeline.

f. Budget and other resources are allocated as planned.

3. Impact Evaluation

Impact evaluation will be conducted to assess the immediate outcomes of the program (Habicht et al., 1999). In this case, impact evaluation will be used to determine if the objectives can be achieved.

For food companies, impact evaluation will be done by checking the sodium content from the nutrition facts label and confirm it through a laboratory testing by shing food sample and use spectrophotometry to analyse the sodium content (Camden BRI, 2011). Laboratory testing need to show that sodium content of the product is <140mg/ serving. For restaurants, impact evaluation will be done through observation of the sauces and condiments used for cooking and their practice in using it according to their recipe. Restaurants need to successfully use low sodium products to be able to get the incentive and “low sodium option” label.

4. Outcome Evaluation

Outcome evaluation will be conducted to assess the long-term outcome of the program (Habicht et al., 1999). In this case, it will be conducted to measure sodium intake of Indonesian adult in urban area that is expected to decline into

<2000 mg/day. Evaluation can be done by conducting a pre-post study with a random sampling method. Sodium intake can be measure through a 24-h urinary sodium excretion that is considered as the gold standard. This method calculates sodium intake by measuring the electrolyte excretion through kidney while excluding other excretion route. Therefore, it reflects about 85-90% and exclude 10-15% of true intake (WHO, 2007).

Unfortunately, 24-h urinary sodium excretion it is not the easiest thing to do. This method will put high burden for the study participant as it demands high commitment for them to collect all their urine in 24 hour and they can only miss one void or their sample will be invalid (Beer-Borst et al., 2022). Therefore, appropriate compensation needs to be provided for participant who are willing to join the study. The benefit of this method is that it is objective since the calculation is not based on participants’ report of dietary intake, so it minimises the response bias as they cannot manipulate it.

In case of 24-h urinary sodium excretion is not feasible due to limited resources, casual urine samples, where participant only need to collect their urine once at any time, can be done as it gives less burden for participants, cheap, and quickly obtained. However, as the content of sodium in urine might fluctuate all day, corrective factors is needed to validate the result. Therefore, a pilot study in the same population needs to be conducted to calculate the corrective factors (Amarra & Khor, 2015).

D. Conclusion

To conclude, high salt intake among Indonesian adult in urban area need to be tackled soon as it causes serious implication to the health of society. As the government and NGOs has previously conducted education and obligated food industry to mention the sodium content in the nutrition facts, intervention in other area involving food industry need to be done. As the problem is caused by eating out habit in which the cuisine used sauces and condiments contains high amount of sodium, the intervention is trying to address the root cause by reducing sodium content in sauces and condiments and promoting it to restaurant so people can eat out without necessarily having high sodium intake.

Bibliography

Abdul Aziz, N. S., Ambak, R., Othman, F., He, F. J., Yusof, M., Paiwai, F., Abdul Ghaffar, S., Mohd Yusof, M. F., Cheong, S. M., MacGregor, G., & Aris, T. (2021). Risk factors related with high sodium intake among Malaysian adults: findings from the Malaysian Community Salt Survey (MyCoSS) 2017–2018. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-021-00233-2

Aburto, N. J., Ziolkovska, A., Hooper, L., Elliott, P., Cappuccio, F. P., & Meerpohl, J. J. (2013). Effect of lower sodium intake on health: Systematic review and meta-analyses. In BMJ (Online) (Vol. 346, Issue 7903). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f1326

Amarra, M. S., & Khor, G. L. (2015). Sodium Consumption in Southeast Asia: An Updated Review of Intake Levels and Dietary Sources in Six Countries. In Preventive Nutrition (pp. 765–792). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22431- 2_36

Andarwulan, N., Madanijah, S., Briawan, D., Anwar, K., Bararah, A., Saraswati, & Średnicka- Tober, D. (2021). Food consumption pattern and the intake of sugar, salt, and fat in the South Jakarta City—Indonesia. Nutrients, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041289

Andarwulan, N., Nuraida, L., Madanijah, S., Lioe, H. N., & . Z. (2011). Free Glutamate Content of Condiment and Seasonings and Their Intake in Bogor and Jakarta, Indonesia. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 02(07), 764–769. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2011.27105

Astutik, E., Farapti, F., Tama, T. D., & Puspikawati, S. I. (2021). Differences Risk Factors for Hypertension Among Elderly Woman in Rural and Urban Indonesia. In YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE (Vol. 94).

Batcagan-Abueg, A. P. M., Lee, J. J. M., Chan, P., Rebello, S. A., & Amarra, M. S. V. (2013). Salt intakes and salt reduction initiatives in southeast asia: A review. In Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 22, Issue 4, pp. 490–504). https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.4.04

Beer-Borst, S., Hayoz, S., Gréa Krause, C., & Strazzullo, P. (2022). Validation of salt intake measurements: Comparisons of a food record checklist and spot-urine collection to 24- h urine collection. Public Health Nutrition, 25(11), 2983–2994. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022001537

Camden BRI. (2011, November). Salt analysis, determining the salt content of foods at Campden BRI. Www.campdenbri.co.uk. https://www.campdenbri.co.uk/white- papers/salt-analysis-food.php

Cobiac, L. J., Vos, T., & Veerman, J. L. (2010). Cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce dietary salt intake. Heart, 96(23), 1920–1925. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2010.199240 Dehar, M.-A., Casswell, S., & Duignan, P. (1993). Formative and Process Evaluation of Health Promotion and DIsease Prevention Programs. In EVALUATION REVIEW (Vol. 17, Issue 2). Sage Publications, Inc.

Elwy, A. R., Wasan, A. D., Gillman, A. G., Johnston, K. L., Dodds, N., McFarland, C., & Greco, C.M. (2020). Using formative evaluation methods to improve clinical implementation efforts: Description and an example. Psychiatry Research, 283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112532

Habicht, J. P., Victora, C. G., & Vaughan, J. P. (1999). Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. In International Journal of Epidemiology (Vol. 28).

Hyseni, L., Elliot-Green, A., Lloyd-Williams, F., Kypridemos, C., O’Flaherty, M., McGill, R., Orton, L., Bromley, H., Cappuccio, F. P., & Capewell, S. (2017). Systematic review of dietary salt reduction policies: Evidence for an effectiveness hierarchy? In PLoS ONE (Vol. 12, Issue 5). Public Library of Science. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177535

Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Examination of Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols., Wartella, Ellen., Lichtenstein, A. H., Boon, C. S., & Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Food and Nutrition Board. (2010). Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols. Phase I Report. National Academies Press.

Istiqomah, N., Astawan, M., & Palupi, N. S. (2021). Assessment of Sodium Content of Processed Food Available in Indonesia. Jurnal Gizi Dan Pangan, 16(3), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.25182/jgp.2021.16.3.129-138

Kementerian Kesehatan RI. (2019). Laporan Riskesdas 2018 Nasional.

Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. (2022). Materi Medsos: Anjuaran Konsumsi Gula, Garam dan Lemak per Hari. Https://Promkes.kemkes.go.id/. https://promkes.kemkes.go.id/materi-medsos-anjuaran-konsumsi-gula-garam-dan- lemak-per-hari

Pietinen, P., Valsta, L. M., Hirvonen, T., & Sinkko, H. (2007). Labelling the salt content in food. Public Health Nutrition, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007000249

Regan, Á., Kent, M. P., Raats, M. M., McConnon, Á., Wall, P., & Dubois, L. (2017). Applying a consumer behavior lens to salt reduction initiatives. In Nutrients (Vol. 9, Issue 8). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080901

Santos, J. A., Tekle, D., Rosewarne, E., Flexner, N., Cobb, L., Al-Jawaldeh, A., Kim, W. J., Breda, J., Whiting, S., Campbell, N., Neal, B., Webster, J., & Trieu, K. (2021). A Systematic Review of Salt Reduction Initiatives around the World: A Midterm Evaluation of Progress towards the 2025 Global Non-Communicable Diseases Salt Reduction Target. In Advances in Nutrition (Vol. 12, Issue 5, pp. 1768–1780). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmab008

Sari, D. W., Noguchi-Watanabe, M., Sasaki, S., Sahar, J., & Yamamoto-Mitani, N. (2021). Estimation of sodium and potassium intakes assessed by two 24-hour urine collections in a city of Indonesia. British Journal of Nutrition, 126(10), 1537–1548. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521000271

Sari, D. W., Noguchi-Watanabe, M., Sasaki, S., & Yamamoto-Mitani, N. (2022). Dietary Patterns of 479 Indonesian Adults and Their Associations with Sodium and Potassium Intakes Estimated by Two 24-h Urine Collections. Nutrients, 14(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142905

Sarmugam, R., & Worsley, A. (2014). Current levels of salt knowledge: A review of the literature. In Nutrients (Vol. 6, Issue 12, pp. 5534–5559). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6125534

Saunders, R. P., Evans, M. H., & Joshi, P. (2005). Developing a Process-Evaluation Plan for Assessing Health Promotion Program Implementation: A How-To Guide. Health Promotion Practice, 6(2), 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839904273387

Subasinghe, A. K., Arabshahi, S., Busingye, D., Evans, R. G., Walker, K. Z., Riddell, M. A., & Thrift, A. G. (2016). Association between salt and hypertension in rural and urban populations of low to middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population based studies. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 25(2), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2016.25.2.25

Tan, K. W., Quaye, S. E. D., Koo, J. R., Lim, J. T., Cook, A. R., & Dickens, B. L. (2021). Assessing the impact of salt reduction initiatives on the chronic disease burden of Singapore. Nutrients, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041171

Trieu, K., Neal, B., Hawkes, C., Dunford, E., Campbell, N., Rodriguez-Fernandez, R., Legetic, B., Mclaren, L., Barberio, A., & Webster, J. (2015). Salt reduction initiatives around the world-A systematic review of progress towards the global target. In PLoS ONE (Vol. 10, Issue 7). Public Library of Science. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130247

WHO. (2007). REDUCING SALT INTAKE IN POPULATIONS.

WHO. (2012). Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241504836

WHO. (2021). WHO global sodium benchmarks for different food categories.